X. Speculations on the Free Schools Movement

I. Is It a Movement?

For decades, there was a handful of radically progressive schools in America. In the 1960s, new consciousness emerged, began many kinds of experiment, turned inevitably to "lower" education. By '66, A.S. Neill’s Summerhill was already popular, giving people common rhetoric to work with, and new elementary and high-schools schools began to multiply. This was also the year of the first one I know to have been evolved from a political context (SDS/REP), the Ann Arbor Children's Community. By late '71, there were some 400 "free" schools. It's hard to say what they have in common, besides some tendency to dethrone old Authorities and foster self-directed learning, and a lot of problems. Though all are reacting against the official system of education, as yet they share no clear vision, let alone mutual allegiance.

Are they a movement? What is a movement? Facing common need, people come together to try to puzzle out a way of doing things differently. In the beginning, they share no clear understanding of their situation and mutual interest, or of where and how to move to build what they need. Always, when mass will bursts out, it stands at first confused and divided, shaking off old mystifications, before it goes on to develop common ideology and practice; or fails in this. The free schools movement, like any other, will flourish to the extent that it develops a collective consciousness that works to extend and deepen itself in the society. Only this can keep it, school by school and as a whole, from being blunted, moving off into dead ends, or being reabsorbed into the dominant system,

Each free school must understand itself as part of a movement, and the movement as a force among counterforces in a culture in which great currents of liberation and repression contend in history. This is hard; we are taught to understand what we do, as well as how we suffer, only in private, isolated, and a-historical terms. People are still trying to describe the philosophy and practice of free schooling in such terms, stripped of their broad social and political consequences and obligations, following the pastoral Summerhill archetype. That's not enough.

2. How Fast is it Growing? How Large Will it Grow?

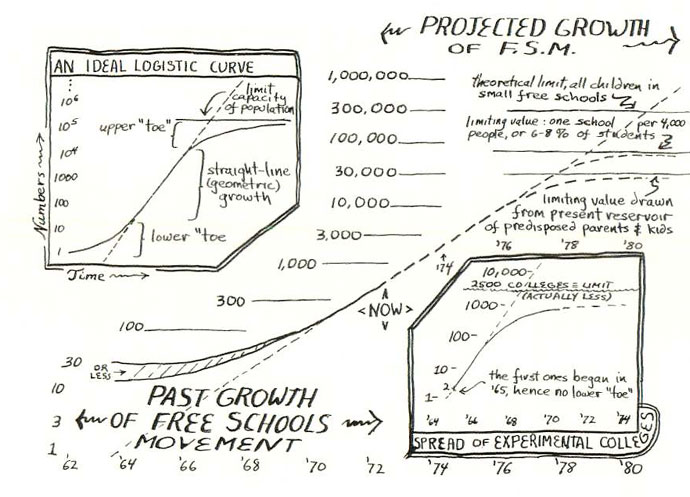

Consider a parallel movement in higher education. The first campus-based free university appeared in '65; by '69 there were 500. They are a population, spreading through a new niche in the social ecology, and are subject to the laws of ecology. One law is that a population cannot multiply indefinitely: its numbers approach some upper limit in time. Moreover, in general, a population increases in a specific way toward its upper limit. Plotting its numbers on a graph against time, we get a logistic growth curve. (See diagram below.)

As the environment becomes favorable, a small, stable population begins to multiply. This is described by the "toe" of the curve. The curve then rises as a straight line, describing a period of geometric (exponential) multiplication – here, increasing tenfold per unit of time. Finally some limiting factor causes growth to level out, in a reverse "toe," approaching its upper limit. (For free universities, the upper limit cannot exceed the number of campuses; the curve has no "toe" because the organism is new.)

Now take the main curve for free schools. It has a legitimate "toe": some have been around for a long time. We are now in the straight-line period. They are doubling in number yearly, and will for some time, approaching one of the limits indicated, unless the environment changes radically. What would stunt free-school multiplication? Radical reform of the public schools. Unlikely within this decade. Economic depression, political repression. Not to be expected on a major scale before '76 (though, like the aerospace elite, many who now feed on affluence are beginning to feel the pinch). By then, the initial multiplication of free schools will be already cresting.

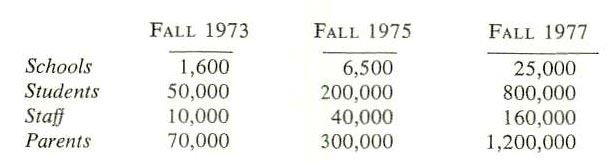

Thus these figures seem plausible now:

(Such graphs are most convenient with the population-axis increasing geometrically, and the time-axis only arithmetically.)

3. Are these figures realistic? Parallels with Free University Growth.

The movements for free schools and for free universities have many similarities. Both are concerned with reforming the educational system by creating alternate institutions. The values and directions of change both try to embody are similar. So are their deficiencies -- e.g., they're as yet unable to re-create the learning of our more technical skills, like the sciences. Each movement spreads by a process of personal contact and media exposure -- which does not so much convince new people as motivate those already prone to make their own examples. As schools multiply and people seek information, newsletters appear, conferences are called, the potential for the internal education of a movement appears. As the density of schools increases, urban and regional cooperations grow among them. After several years of local work, speakers and traveling organizers appear, drawn from experience in the movement itself, to help it build and circulate its understandings. (Upon the careful cultivation of such italicized

Higher education is everywhere pretty much the same, so each campus is the potential host of a Free U. Free U members seem mainly to select themselves by psychological predisposition: by their need and readiness for freer ways of learning. Their proportion in any college, plain or fancy, seems remarkably constant: some 6 to I0 per cent of the students.

If the parallel holds' consider the 44 million kids aged six to sixteen. Figuring only for nonreactionary, white, middle-class families, some 40 per cent of the total, 6 to 10 percent predisposed works out to I million to 1.5 million white, mildly liberal kids, as a first base for free schools to spread through in the next few years, (This estimate points up the racist/elitist character of the present movement, one of its principal problems.) More broadly: each town, each school district of over 500 students, each ethnic group or neighborhood of over 4,000 persons, has enough predisposed/receptive parents and students to spawn a small free school. So a vision of 50,000 free schools is not unreasonable.

4. Teachers and Parents

There are now battalions of frustrated teachers, mostly young, looking for something better to do than teach in the System. More and more put in a few years, find it unbearable, drift unengaged. Forecast for the decade: the public schools will grow worse. An unstable economy will refuse their rehabilitation; they will continue their development as battlegrounds for the society's racism; as the political climate grows ugly the reins of control will tighten within them. Meanwhile, deep trends will continue, moving many from technological to human-oriented jobs; from detached to socially relevant work; from "straight" jobs in bureaucratic hierarchies at work determined by others to work of their own choice and making, All in all, the seventies will see no shortage of people ready to staff a first great wave of free schools.

In general, these people will be making heavy changes in their own lives toward more integral ways of relating -- sexually, emotionally, communally, ecologically, politically. The nature and difficulties of these changes will strongly influence what they can or want to do in free schools, and how they will go about teaching.

The same will be increasingly true of free school parents. We must see them not only as individual people in change, but as a changing class. It's hard to measure the more intimate aspects of their change. But some social aspects are clear enough to warn us that the present crop of some 20,000 free school parents gives us only a limited idea of what to expect and plan for in the future. The great majority of them are over thirty, and almost all ended their undergraduate college experience by '63, or at the latest by '65. That is to say, before the first campus sit-ins, hippies and the Haight, Vietnam-as-issue, the Beatles, grass and acid, Panthers and Women's Lib -- back in the palmy days of civil rights, when Amerika and her institutions still seemed open to liberal change.

Some were relatively radical once, or since. But the college experience and the growing up of all of them were qualitatively different than these were for the generation coming to adulthood in the late sixties, from whom will come most of the parents who will build the free school movement to massive proportions during the seventies, Consider a member of the Class of '68, who has a child in '70, who is school-age in '76. In '68, about 4 percent of college students participated in experimental colleges, and 5 percent tutored "disadvantaged" children -- that is, involved themselves personally in experimental education; 20 percent took part in demonstrations against some aspect of the authority of the State and/or the Educational System; 20 percent smoked grass, one in twenty did acid, Fortune estimated 40 percent were in basic sympathy with the "goals of the New Left."

By 1980, there will be over 30 million parents of school-aged children in the twenty-seven to thirty-five age range. Of these, more than 2 million will have been directly involved in counter-education: 6 million in organized demonstrations against illegitimate authority; 10 million in psychedelic drugs. These estimates are low; they take no account of the way all the curves of involvement are soaring -- 2 million turned out for Cambodia/Kent alone, the year the Weather-people went underground and the newspapers blanked out eight bombings a day nationwide. There is less sign now than a decade ago that our institutions are open to the changes we want. Surely many parents will commit their kids to free schools if the form continues to be viable.

5. Out of a Changing Substance: In a Changing Climate

At each college now the incoming freshmen are markedly more life-radical than the seniors, Change piles upon itself that rapidly nowadays, and will do so in the free schools movement as well. The movement will expand through the seventies on a wave of people who have been through confrontation politics, psychedelic drugs, encounter and hip culture. We plan for the future by studying the changes of the present, and any projection for the movement must take into account such radical shifts in experience and perception, the suddenness with which they happen, the sharpness of their later echoes.

The gamut we must deal with runs from sex to politics. Presently the edge, in the broad domain of sex, is like this for people in their twenties: women's liberation spreading, gays coming out and straights investigating their bisexuality, group marriages, public nudity, legitimate abortion, open sexual liaisons and non-private-property attitudes about lovers' bodies. All this will show up integrally in the curriculum/process of free schools. For in live contact with students, the forces of change running through people's lives cannot fail to be expressed. And in this matter of sex, as in many others, the free schools will be ideal experimental vehicles -- small, highly flexible and various, more or less removed from larger social control -- for testing out the integration of new cultural knowledge/experience into basic education. Well in advance of this wave of sexual opening, the movement should begin to discuss its nature and impact, more thoroughly than Neill has done. But we probably won't, and each school will be left to understand and struggle with sexual matters mostly by itself.

All the openings of the sexual edge have their political aspect, and politics will follow after any opening of sexuality in education -- think about nudity, and getting permits from the county building inspector. More broadly: the free schools movement will grow and be shaped in the political climates of this decade, conflicting thermals will feed it and stunt it. Any projection must predict the weather during the season of growth, You don't need a Weatherman to know which way the wind blows. For most of the decade, the polarizations of Amerika will increase; there will be more violence, especially of a semi-organized kind, and a coldening climate of political repression, directed at all forms of liberated behavior or doctrine. For this is the decade when it begins to get hard, after the easy dreams of the sixties: when Amerika's true resistance to change, and for each of us our own, begins to come into the open.

6. Tension, Co-Optation, Containment, Repression

Free schools will quickly become a major alternative to the public system, and will drain from it more and more of its innovative teachers, responsive kids, and certain classes of parents. To this extent, the mainstream system will grow even less adaptable, and polarization between the two will deepen and grow bitter, in style and politics.

But there will also be a blurring of the lines between them. The presence of an alternate system, covering all levels of education, will cause the mainstream system to adapt competitively. in the classic way -- by modifying and adopting the lesser pieces of the radical program, as fragments stripped of their broader implications. Thus, we see already some loosening of curriculum, schedule, learning-group size; some fuzzing of the grading system; expansion of teaching into affective domains; and so on. For the next five years, we can expect a deluge of articles in national magazines boasting the modernization of the suburban junior high.

But some lines cannot be crossed. So long as schools serve to prepare the young for the present industrial machinery, they must teach them to defer to experts, obey bureaucratic authority, work unwillingly, specialize narrowly, and maintain the chauvinisms of class, race, sex, and age. Whether or not the mainstream schools seem to come more under parent control, and no matter how much ecstatic new technology is used to "enrich" them, they must continue to be staffed by a corps of teachers trained to pass on the ruling orthodoxies of mainstream culture -- consumerism, sexual repression, nationalism, idol-worship, etc.

Enough people will not be satisfied with this to cause a further adaptation -- an attempted "encysting" of the alternate system within the mainstream one, to neutralize its effect. Within many urban and suburban schools will grow "free" sub-schools: and many local school systems will sponsor experimental campuses. Together these will constitute a sophisticated addition to the tracking system. and, whatever their "freeing" of the kids, will preserve the principle of elitism. Unless students and parents make something else happen, the effect will be to isolate change-energy and protect the larger system from transformation.

A cautionary tale, from an earlier movement: By now the campus Free U's have grown somewhat stale. College administrators welcome them as "constructive," i.e., non-threatening. And they are right. Such groups have needed space, resources, legitimacy, accreditation, and have sought these mostly from the established institution and in its terms. To be tolerated, they damp their potential thrust for change in their host institutions and in social structures, instead orienting themselves to personal change and private experience. Where they do not, as at San Francisco State, multiple forces attack them.

Independently founded free schools will face the same pressures, the same blunting of their thrust. Powerful undertows of need will pull them to depend on cooperation with the great urban bureaucracies. The price of support will be a soft repression, a biasing of goals, standards, and processes. Only the development of sharp collective consciousness and community-based independence from the mainstream system can keep open the possibilities of social reconstruction inherent in root educational change.

Here's a paranoid scenario for the next few years, as free schools pass their founding flush and begin grappling with the problems of how to move on:

A network of periodicals from the educational underground will arise to testify to a dozen regional cooperations. (First versions of these cooperations are evident already in Berkeley and New York, and prototype journals include New Schools Exchange Network, Ed-Centric, and Outside the Net.)

As individual free schools are doing now, soon many local and regional cooperations will work hard on grant proposals to foundations and Federal agencies. Most of this work will be wasted. Only a few small family funds will respond well, in non-constraining ways. The giant foundations that deal in education, like Ford and Carnegie, will perform like the Government agencies (OE, NIMH, OEO) to implement official social policy, funding what's "safe" and encouraging its dominance in the movement, judging in a sanitized style who and what programs are "responsible" enough to support and what constitutes "results."

As it becomes clear what massive discontent and radical potential are represented in the free schools movement, both private and Federal agencies will bestow demonstration grants in the $200,000 to $2 million class upon local or national cooperations that are taken to represent the most "promising" features of the (anarchic, disorganized) movement. If the parallel with the higher ed reform movement holds, these grants will be badly administered, politically crippling, sexist, and racist; and the major part of the funds will be absorbed in administrative unwork. Agencies already cooperative with the private and Federal funding structure -- like the Antioch-centered Establishment of experimental higher education and the Berkeley city schools -- will be chosen as the conduits through which funds will flow to satellite "independent" free schools programs.

This Establishment-sponsored ''vanguard" will be rendered larger than life by the selective attention of the mass media. Thirsty for official recognition and support, the mass of free schools will come to shape their philosophies and practices in accordance with this amplified image of what succeeds. In polarized opposition, we will see a "small, hard-core radical minority," most defiantly countercultural, some with hard left politics, probably fairly isolated from each other. Most free schools whose spirit is that of Summerhill will be readily absorbed as ancillaries to the public schools, as most private schools have always been, and will see no clear reason to resist this. (In this lack of oppositional spine will appear the consequence of the incompleteness of Neill's philosophy, which deals only with community that frees the individual. and not also with the general reformation of society. )

In the same way that Young Americans for Freedom are now multiplying on the campuses, so soon, in city and country, right-wing groups will form and act more openly in lower education. They will advise and be advised by local and Washington politicians, not all Republican, who will also be their avenues of access to FBI and other "subversive" files. Such groups will mount campaigns, locally and nationally, against free schools of all kinds and levels. Their viciousness will rise in direct proportion to that of the hardhat/racist backlash as it continues to unfold. Thus hand-in-hand with liberal "encouragement" of the free schools movement, we shall see its attack by a broad spectrum of overtly repressive forces -- a powerful combination of push/pull to bring it into line

As it becomes recognized as a massive leading edge, the free schools movement, like ecology, will be courted by politicians and made the subject of Presidential rhetoric and some legislation. By 1976, the threat of its unregulated growth will lead to major state or Federal programs for redistributing education tax money for parents' "free" use, in the form of tuition vouchers. At best, this could open an enormous freedom for experiment (at the cost of allowing much of Amerika to continue at will in racist education). But there will be conditions, of course -- beyond the powerful conservative effect of giving control of the vouchers to parents rather than to children. Free schools will have to conform to certain regulations, not only of plumbing but of practice, to be eligible for voucher redemption. The tame will flourish, the wild starve.

Those that will not be domesticated, that deal openly and deviantly enough with, say, sex-drugs-and-politics, will be harassed by inspectors and closed after arrests, or dynamited in the night.

7. Beyond Free Schools

So far, I've spoken of the free schools movement in terms of its being a growing collection of small, relatively autonomous experimental schools. As such, it has material needs, a political identity, philosophical and political problems, etc., all of which we are only beginning to grapple with.

Yet this institutional facade, the domain of our immediate necessities and decisions, is also an illusion. For I think that free schools, however we now conceive them, are a transitional institution, and that the movement whose present frontier they represent is in its essence trans-institutional. In concert with other current group experiments, they mark an early stage in a revolution of social forms that will transcend our present understanding of what institutions are and how they function.

We are engaged in a profound transition -- old news, but it hasn't really penetrated our consciousness. All of the great divisions articulated into our lives -- work/play, rich/ poor, body/mind, male/female, subject/object, religious/ secular, and of course, teacher/student, learning/action, school/world -- all these and more shall be broken, melted and reconfigured in a more integral harmony, if Man is to survive.

Though we live from day to day on the level of hassling with the building inspector, we must seek such terms as these to make sense out of what we are doing, out of the changes we go through in our parts in the Change that is acting through us. There are no two ways about it: no terms less broad will do. We would be mistaken, for example, to go by our past experience with new educational forms -- the fraternity, the public school, the land-grant college, the kindergarten -- and expect that free schools too will simply multiply to saturate their niche in the American institutional ecology and then persist for a century or so as a stable, well-defined institutional form.

Rather, I think, we shall come to see them as a dew in the meadow of change, each drop dispersing again into new forms as the sun cycles. Already free schools are noted for being short-lived. Universally, such May-fly life is taken for failure. But I think it may equally mark success. For, to the extent that a school is a free space for change, its operations transform its members, carrying them to new consciousness of what is and new conceptions of what is to be done. Such transformations cycle in the periods described in Chapter VIII. That the average life-span of a free school is now eighteen months is no accident.

So, if we are not overeager to recognize a form in which we can rest our action. we should expect to see people found free schools or work in them, continue transformation, migrate alone or as whole groups into other cooperations, which may no longer be called "schools." From this perspective, whether individual free schools persist or disappear is not important, as long as each provides an integral period of experience for all its participants. Free schools are probably best seen as Kleenex institutions, to be made, used, and discarded (unless we escape our old notions about, and commitments to, institutional permanence, we will be in for much agony in such decisions).

Yet though their flesh change fast, free schools will be with us for some time. The estimates above for the spread of free schools presume nothing about the endurance of individual schools, much about the multiplication of a consciousness against a uniform background of need. Overall, these free schools will function as transition valves, arenas of experience leading their participants into new adventures. Many may be decade-stable as continuous loci of transition for rapid generations of learners.

The Law that says making change changes the changers leads us, alone and together, through clear sequences of evolution in consciousness and action. These sequences, still developing, are common and beginning to pass into folklore, though they have not been written about much. They are compounded from successions of experience on the major learning frontiers of our time, and seem on the whole to be leading people toward the undifferentiated seed of a new form -- a group at once family and pride, cooperative work unit, playgroup and mutual school, doctor and priest of its members: a flexible intimate society that supports and frees its people to assume and reconfigure all the necessary human roles, and that is itself protean in its manifestations in the larger society, appearing, in our present terms, for a while as a school, as a sexual consortium, as a laboratory, as a dispersed collection of friends.

Toward this seed form communes, political action groups, media collectives, and other new cooperations are now mutating. We should expect each free school also to mutate in this direction as experience enlarges its perspective. Indeed, if one critical imperative of our change is to recreate so deeply the nature of the groups in which people are embedded, a free school which focuses on relevant learning for all its participants (not just the kids) may proceed on this metamorphosis quickest of all.

8. Ageism, Free Schools, and Conferences

One evening, at an early conference of free schools, Jackie Perez started talking about youth collectives. Already ten-year-olds are gathering in them in preference to home, she said, and soon we shall see children much younger choosing to develop in environments not dominated by adults.

She didn't get much chance to draw out her argument. Umpteen people jumped her verbally. Their evident passion indicated that she had touched a raw nerve, the key psychosis (in the strict sense) of the free school movement -- the belief that kids are uniquely dependent upon our efforts as "adults" to construct the circumstances of their education for them.

There's no point arguing whether younger people "need" older ones: the unfondled infant grows up cold. The deeper truth is that we are present in their world, and they will learn essential things from us whatever we do. In free schools, as in any others, we will be conscious only of fragmentary and superficial aspects of what it is we are teaching them by the ways we live. This is no argument against being purposeful about the educational process, as best we can. But it is a dangerous narrowness of vision to mistake the school we construct for their actual School.

In its altruistic focus upon providing for the needs of others, the free schools movement threatens to become the ultimate liberal trip, You will recall: we started out Doing Good for the oppressed Negro and others of color; went on to Do Good for the Vietnamese, as best we were able; and then turned to Doing Good for the poor whites, the culturally oppressed straights, etc. Now we are Doing Good for our own oppressed children. God forbid they should reject our attentions -- we might have to face the prospect of doing ourselves some radical Good.

I don't know how many people have told me that the problems of free schools are more with the parents and teachers than with the children -- that free schools are generated as much in response to their needs as to those of the kids, and serve as vehicles for the acting-out of adult fantasies and therapies. This is to be expected: it testifies to objective social conditions. There should be no need to rehearse again the circumstances of our own oppression: we each are discovering them, and every open space calls on us to make the changes we have held back from.

Adult needs must be openly recognized, and their learning co-equally focused upon, rather than acted out covertly or vicariously. Only thus can the space of children's learning be freed from that oppressive control that comes from living our lives through them. Children need not only the contexts we create, but also freedom from them -- the more so since much of our learning these days is remedial, addressed to destructive ways into which they have not yet been fully acculturated.

Their ultimate school is our own lives, plus what else they discover. In seeking to benefit them, we would do well to tend to ourselves. If we are involved in creating conditions and ways that fulfill us as humans in a web of life, I daresay their education will be fairly well provided for, whatever institutional arrangements we may make. Surely the most profound teaching we can exhibit to the young of an age of Transformation is our own example as persons actively engaged in the struggle to re-create our own lives -- internally, in groups, and in the larger social order. (In the politics of change, all the skills customarily thought of as being taught in school, from mathematics to welding to emotional control, fall into the perspective of this struggle, and will be learned in terms of their use or misuse in it.)

But see – again, and so easily, I fall back toward the terms of ageism, speaking only of adults as key to children's learning, rather than equally of the converse truth, It's only natural: I'm much more conscious of the things I have to teach my son than of what I might learn from him.

My lopsided consciousness is shared by many. At a conference of some 300 people, there were a few mid-teens and maybe a dozen children from two to seven, plus an eleven-year-old. From the age-distribution, you'd never have known that it represented a frontier movement of education, in which the young were to be newly and integrally involved. It was like any movement conference –- say, the anti-war movement, or black liberation, save that in these young teens would be better represented.

I want to look at this conference as at a school, and in terms of its ageism, for it was a learning-exchange among people trying to make new sorts of schools. Yet younger people neither shared in its planning nor were consulted -- though it was brought off by people in their twenties who are intimately involved in free schools. The presence of minors wasn't actively discouraged; but invitations circulated mostly among adults, and the fee structure was inhibiting. Nor were there, in the conference program, topics of interest as the young would define them, nor space for these to be generated, let alone actual free-school students whose presentations were featured.

Such political analysis may seem a parody. But it is necessary in some form to discuss responsibly the workings of a movement of many people whose lives are conjoined in experiment -- a movement whose development is still entirely in the control of a minority, one distinctly political in having vested interests of power and limitations of consciousness which it cannot transcend alone. Be forewarned: this is the sort of analysis we shall shortly have to contend with from children themselves, who will take its terms with deadly seriousness.

It's not just a cute coincidence that the 1971 Berkeley elections, which brought radicals fractional power for the first time, and the first school board campaign by a representative of a regional coalition of free schools, also brought the first Children's Liberation platform, equally conjoined with the others to form the broad program of the April Coalition. The Kid's Lib platform was written by a ten-year-old. I felt this uneasy chill, listening to him rap down the same kinds of terms I am rephrasing here. But maybe he's a freak, maybe he'll go away; as long as there's only one of him, there's no real problem. Listen: write me, will you, if you spot any more?

Back to the conference, As usual, we acted it out mostly in terms of old visions of what our schooling together should be like. Had it not been exclusively adult-centered, would it have been so dense with schedule, having neither recess for intimate interaction (save at meals) nor playground (save for two small body workshops)? Mostly people gathered in crowds to hear a few Names hold forth and to quiz them. I was a Name, I guess, and found that I couldn't help but contribute to the hierarchies-of-wisdom game, running on in the same old male rapping style -- so retrograde to find it entrenched in a movement this rich in together women.

As conferences go, this one had a fair amount of open space, and several strong workshops formed around freer processes to deal with practical matters relating to a mass democratic base (like organizing regional cooperations of free schools and communes). Most important was the ad-hoc radical caucus that formed to tackle survival strategies. As the first manifestation of its sort (that I know of) in the free schools movement, it initiated the first protest against the present authority-structure of the movement, already well developed and powerful in its influence. In the main session the second day, this caucus presented the problem of a few authorities speaking for the many involved in important work; and demanded that personal profits made through connection with the movement be plowed back into it in substantive ways. A new stage of movement consciousness was perhaps beginning.

But this spontaneous political drama, and the body workshops, were the only "classes" in this school that were not of a long-familiar sort. The dominant mode was argumentative; only rarely did group energy flare in the intensity of the circle of testimony in which experience is shared and distilled. If free schools are developing new consciousness about educational process, it has so far shown up in conferences only in their looser structuring, and not in organized effort to bring people together around newer modes of action and interchange.

There are newer modes aplenty abroad, and good reasons to use them. Any frontier movement ought to be reflexive, ought to turn the full force of the understandings about educational process now available to us upon its own operations, and serve as the laboratory for its own best experiments, making possible a different order of business.

For there was a different order of business, I am convinced, that we came there for but found unlisted in the program -- some business of the spirit, increasingly urgent, but only vaguely and imperfectly transacted through our actual categories of conference-dealing plus that one flash of political consciousness. I don't know how to name it. It has to do with being involved together, interdependent on the edge of an uncertain future; and with levels of consciousness, allegiance, and commitment. (Secretly I think it is the birth of a people's spirit; but I am trying to be sober here.)

This business of the spirit reveals itself to us in shared experience, in group ritual. But it is not much furthered through the group forms of the conference -- purely verbal interchanges, passive attendance to art, and dinner in the cafeteria. Better vehicles would be: campfires, rainstorms, building something together, making music together, playing with an ample video feedback net, centering the occasion on the actual birth of a child, reverencing some change in the natural or human season -- almost any collective action not in the male tradition of harsh light, utilitarian discussion, and rhetorical argument.

Or we might bring in the younger people, and work with them in learning new forms and new ways. I keep coming back toward their perspective, to see how far we are yet from an integral advance. By the second afternoon of the conference, after nearly having a breakdown the night before when it came my turn to sit in the Authority chair and try to keynote some humane version of the old drama, I had had it with words: I couldn't get it together to go hear Kozol talk. I'm still somewhat sorry, for I admire him so and have never seen him in action, and I heard he was fine that session. But I was obsessed by this notion that what people learn, in schools, conferences, etc., is not only the cognitive content of their transactions, but also the continuous social lesson of its forms. A bit freaked by seeing the old lessons endlessly relearned, and weary of the proliferation of merely-worldly words among people coming to care deeply for each other, I let Beth, a gentle lady not given to rapping, lead me off to play with the children.

And there they were, the dozen or so youngs of this free schools conference, off by themselves, away from the meetings in which they'd be indifferent nuisances. Usually some relevant mother was nearby, doing the standard duty. But for the most part they were being attended by an eleven-year-old who had taken their care upon himself, and all conference long was shepherding them in games (while in another room Jackie's remarks, about growing consciousness among youngs, were being greeted with consternation).

We settled in and made a little music. Then somehow, quicker than a wink, I became the ferocious Nose-Kissing Monster, and the Shepherd organized great monster-hunts among his flock, for an hour of squeals, chases, and kissing tumbles. My first monster, I had thought him up only a week ago, while snuffiing Lorca: this was his first tryout and a grand success. I had never before realized how eager children are for a little monstrosity -- not just any monstrosity, but one with some grace and control, funky and real enough to test themselves against, yet with the intelligence to be tamed, and not immune to reconciliation.

And aren't we all the children of a monstrous fantastical age, needing to grow together by our versions of such ritual? I remembered daring the National Guard in Chicago, running from the shotguns in Berkeley, an endless rain of bombs over Indochina. Where are our monsters with the wisdom to yield; where the tribes against whom we test our bravery yet with whom we are united in the festivals of the Great Spirit? And what of the meeting rooms of this conference -- in what thin way were such collective needs met by our exchanges of opinion there? Were the political theater or the sharp questioning of Name speakers our ways of organizing a monster-hunt? And where was the kiss?

Crawling on the floor, my clothes instantly filthy, I saw the conference as a school from the children's perspective. Here they were learning again that to be a child and to be an adult are pretty unrelated occupations. To be an adult and meet about schools is to crowd into a stuffy room and talk talk talk for long hours at a time, not moving your body at all or shouting or whispering or eating or touching anyone else (but maybe laughing a bit and a few hugs at the end). This is what growing up and becoming serious means. They would get the same image if our business were real estate. Why should they be interested? But what they would dig doing all together would be something more emotional and active; and so would I.

See, I don't think this business of learning from children is just a romantic fancy; nor is what we have to learn from them just some humane redecoration of the rooms of our consciousness. That marvelous person Margaret Mead has described one cultural transformation that is upon us as the passage from post-figurative to pre-figurative learning -- that is, from a condition in which adults transmit the entire body of each child's knowledge, through our present stage of increasing age-democratization of the learning process for the young, to what will be necessary for the dynamic stability of a culture of continual change: adults learning major life-lessons from their children, who will lead them in adapting to changing conditions of the material world and of human reality.

Well, that change goes deep, I don't have to tell you. (The youth catalyzation of the civil rights and antiwar movements, and kids turning their parents on to grass and encounter, are only quaint first expressions.) In its fullness, our conception of the nature and function of an educational system will be overturned. And in transition, each of us will constantly be confronted by opportunities of learning -- for growth or for survival -- for which our culture never prepared us.

So we should prepare to meet with our children in strange ways, not least because for some time to come much of our relevant learning must proceed along lines which were dropped or repressed during our own childhoods. The free schools are a laboratory to work out the forms of these meetings, and through them will evolve toward fully democratized and pre-figurative learning communities. But that is a long way off. For now, I could stand to attend a conference designed as much by the younger members of free schools as by the older, integrally, for our mutual learning. Though the kids might get us to do something weird, like make up banners or ceremonies.

Return to: Top | Next | OLSC Contents | Home