23 Nov 07

Thanks Giving

(Good News Comes in Twos)

Well, that's it: I'm out of here tomorrow, after only 26 days of being leashed to an IV drip-pole in a small cell. They have killed me preemptively and then brought me back to life, as a chimera. My sister Devora's stem-cells planted themselves in my marrow – still so choked with fiber that yesterday's large-needle biopsy could not suck a drop of fluid, only fiber and bone spicules – so vigorously that formed cells began appearing in my bloodstream by the tenth day after transplant. By this sixteenth day, my neutrophil count is well above the danger line, my platelets likewise and rising, my red cells – or hers, really; there should be special pronouns for chimeras – are slowly coming on line, and all the other types of white cells seem to be flourishing – including her fearsome T-lymphocytes, which would be chewing up my skin, guts, and liver, were it not for the potent Tacrolimus (1.5 mg/day) that holds them in check, raises my blood-pressure dangerously, and depletes my electrolytes so much that I'll be spending hours each day dripping seven grams of magnesium sulphate into the Hickman blood portal dangling nakedly from my chest, until who knows when.

This is to say that I'm hardly out of the woods yet. My body and her cells will take a long time to learn to live together, needing such help for at least six months, more likely a year, maybe longer. Drugs will control my blood pressure while we wait to see how nasty her T-cells will be and how soon they might become domesticated. Maybe progressively less Tacrolimus will be necessary, leaving me to taper off the anti-hypertensives and needing electrolyte transfusion only every other day, twice a week, once, till we finally adapt. But so long as this powerful immunosuppresent is holding her T- and B-cells in check, I'll be vulnerable especially to fungal infection, for these are the first-line defenders against it. To smoke a joint is to court death from a mold-spore grown on nutritious bud and sucked into my undefended lungs. My hematologist took special care to tell me about the lad who died that way on this ward. What a nuisance!

Even so, to be released from hospital is a milestone indeed, and I'm glad and thankful as can be.

*****

Real though the dangers I still face may be, I feel like a charlatan in brandishing them above. For my whole experience with treatment so far has been of quite different character – bizarre, surreal, a cakewalk, an easy skate over terrifying depths, more nearly a comfortable vacation than the grueling ordeal anticipated by so many of my friends, and by me, to the core.

I came to hospital expecting an ordeal of chemotherapy, an unusually slow process of engraftment as my sister's cells struggled to establish themselves amid dense fibers, a prolonged period of profound neutropenia leaving me unusually vulnerable to potentially-deadly infection, not only from visitors and the hospital itself, but from myself as my own worst danger, fecal bacteria entering my bloodstream through a tiny tear in diarrhea-ravaged tissues. I had girded for this as well as I could, my first goal being simply to get out of here alive, not be among the too-high percentage who die in hospital rather than later. I hoped to be well enough to leave by my birthday, December 15. How disorienting it is, to be sprung free in hardly more than half the time I expected, with no price to pay!

My expectations about chemotherapy had two roots. One came from deciding, with my hematologist Jeff Wolf, to go through the punishing process of a full course of myeloablative ("marrow-destroying") chemo, rather than "mini-ablative" or non-ablative preparations for transplant. Though these have been coming into fashion for good reasons, we chose the more punishing protocol for a better chance at reducing the malignant cells hiding in my fibrous marrow. Stem-cell transplants are only recently coming to be tried with people over 55, even with kinder preparation. Wolf's colleagues thought it too risky to try full ablation on a fellow nearly 68, no matter how robust he appeared. He was quietly jubilant when we received the organ assessments – lung exchange capacity still above normal, heart ejection fraction fully 75% -- that convinced them I probably could take it. Me, I didn't care about the punishment, I had my eye on the prize.

The other root of my anticipation lay in accompanying Lorca through chemotherapy, twenty-six years ago. Reading up now, I learned that cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) had only recently been displaced from the most popular protocols for conditions related to mine. I remember Cytoxan well, and Adriamycin too; I only forget which one had him vomiting for a day and a half despite the anti-emetics that stupefied him in between spasms; and which tapered off after only eighteen hours, with the walls of his stomach beaten so violently together that after the third hour small flecks of blood came to decorate each scant upheaval of pale green gastric juices.

So I was glad to learn that Busulfan, a newer kind of ablative drug, had replaced Cytoxan as the partner of fludarabine in the "Flu-Bu" protocol Wolf offered me. They told me that Bu was much kinder on the body, which mattered less to save suffering than because less punishment meant less chance for aggressive Graft-versus-Host (GVH) disease after transplants took. They said also that anti-emetics had improved greatly,since the era when the best we had to offer Lorca, after he refused any use of cannabis because his dad was such a pot-head, was Torecan or Thorazine. Even so, I was braced deeper inside than I could reach, to spasm as he had and bear it, for the sake of life.

my environment (note drip pole)

Imagine my surprise then, and growing sense of unreality, as my treatment went on. The day after I entered and they put the Hickman cather in my chest, my intravenous chemotherapy began through it, delivering a round of Busulfan every six hours for four days, and five daily rounds of fludarabine, hammering my marrow and stressing my organs. And I felt nothing. Their cocktails of anti-emetics and other experience-softeners, and the good fortune of my own constitutional responses to these toxins, left me touched so lightly that I felt myself to be on the placebo branch of some protocol test until after the nineteenth cumulative round of chemo. Finally, after each of the final two rounds I had one transient spasm of break-through nausea, lasting only a few minutes and light enough to be dispelled by rubbing acupuncture points in my hands. One brought a dry heave; the other produced a spoonful of actual juice, to prove that I had puked.

And that was the sum of my immediate suffering, from my whole course of chemotherapy. I can hardly say how unreal this felt.

******

During the next two days I rested, while my body metabolized the remains of these toxins sufficiently to not endanger the stem-cells I was to receive. So much Busulfan was excreted through my skin after every round that I had to shower repeatedly to make myself not dangerous to touch. Though I hadn't felt affected, I suppose I was recuperating in mind and in the rest of my body, even as the consequences of chemo-destruction continued to unfold in my marrow and other fast-growing tissues. But I hardly paid attention, for I was going nuts with computer problems.

I had meant my website to be up before I entered hospital, so that I could work intensively on its contents here. No such luck; I couldn't get the riddle of access to my provider's server sorted out until after a week here, from mishap on their end and misreading on mine. And even then I couldn't use it, as a mischievous malady had gripped my new laptop, stuffed with all my home files and work, perhaps even because of the way that I'd stuffed them, It disabled my access to drives, danced abortion unpredictably through various programs, destroyed two pen-drives in a row when I tried to protect data. Penned up here, naïve and rattled, I reached out too futilely for help as its damages morphed and became harder to describe.

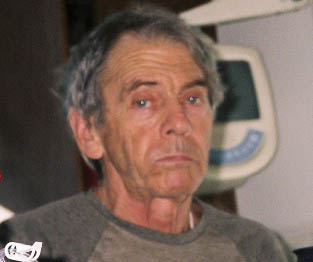

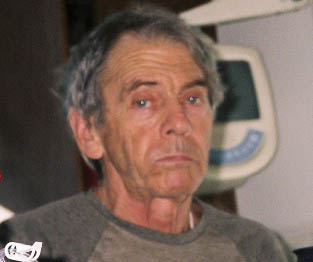

at the computer, nice wide screen (note drip pole)

Short of scrubbing the hard-drive clean and reinstalling everything, cautiously, bit by bit, which I scarcely felt safe in doing or had time for, what could I do? So mostly I worked away at the website's contents on my desktop, in between rounds of chemo, editing forms and putting in basic links. On these rest days I hacked away some more at the problem, but stuck mostly to editing and markup, where I could feel I was getting something done even though my site remained a dream. Need I say how frustrating this was? In truth, such problems bedeviled me much more than the chemotherapy. One might think it good that they distracted me; but I'd much rather have been distracted by the work I was burning to do.

On my blog, I'd compared my coming experience in hospital with my time in jail forty years ago, in terms of the peaceful productivity I hoped for. I do think I'd have achieved that, if it weren't for computer problems; but the comparison was apt enough in other ways. Only in jail, and less so there, have I led such a regimented existence. During my first day of chemo, I received twenty-three visits from sixteen staff, breaking the clock into sub-hourly fragments as their talk and actions introduced me to the regularities of food-getting and blood-letting, cleaning of self's cavities and the cavity of my cell, and so on, that would govern my experience for the duration. During the following days, these played out only slightly less frantically. Four or five times each day, I was infused with multiple agents; four times twice around the clock my vital signs were read, and often in between. Plates of cooling food appeared periodically, commanding attention; monitors checked off my multiple showers and rinsings with alkaline mouthwash, and so on – plus regular blood-counts and irregular titer-draws, four scheduled dosings of oral medications even after chemo was over, daily rounds and afternoon visits by the attending hematologist and my wonderful nurse-practioner Lisa, laggard exercise sessions, and so on … In time, two dependable periods free from interruption appeared; but as these were from 1:00-3:30 and 3:30-6:30 am and it was hard to sleep during the day, I could hardly use them.

yet another transfusion (platelets are tan)

Lord, is it any wonder that I never found time before this even to set down such a list – let alone to respond to virtually any of the dear and wonderful friends and strangers who sent me their regards and love by one avenue and another? For to write even the simplest genuine response to another person was to open myself to more feeling than I knew how to express, and required me to turn from my center outward -- while I was so buffeted by this regimented chaos of interruption, above the deeper chaos within, that all I could manage was to hold to my center in the fragments of free time. Forgive me, dear friends, this is all I was able; I would have spent an hour with you each time if I could.

Even my own writing took deeper focus than I could manage, and my blog kept on frustrating everyone who looked for updates, until Karen provided what I could not even blurt out, a brief, straightforward report of what was going on with me. Only such disability could have delayed me so in fulfilling my promise to report the second of my three magical dreams, so here it is now:

[My Second Wonderful Dream]

I'm in the basement of a huge shopping-mall, or rather on the first floor down from ground. There are stores of various sorts in corridors extending one way and another, but what draws me is one near the center, where small flats of dusty mineral specimens spill into the corridor, as they do in small rock-shops the world over. Looking up, I realize I've stumbled upon one indeed, or rather, on a new one preparing to open for business, for through doors inside I glimpse people carrying crates from one room to another, setting up counter displays and bins for the customers they expect. No one's ready to talk with me, but no one seems to mind my looking around; so I finger the small change in my pocket while I cruise the pricier specimens in cabinets, as I've done so often in life. Room opens to room, the place is huge, goes on and on, with ranks of sliced mandalic geodes, calligraphic slabs, columns of watermelon tourmaline, towns and cities and metropolises of crystalline quartz … Passing the great display windows, with museum-quality specimens of argentine and cuprite, great spears of aquamarine, I realize I've come to the mother of all rock-shops, with more stock than all those I've seen in my life put together, in glittering crystalline displays pulsing with light, refracting rainbows from barely-imagined treasures, all open to my hungry gaze for worship even though I can't afford more than the meanest, still a miracle in itself.

I woke glowing, vibrant with energy, awed that a vision of such beauty and power could crystallize within me. For two days I bore it around in silence, its images pulsing vividly behind my outer gaze, still energizing me strangely, without pausing or needing to wonder whether or what it might mean. Until I told Karen, who gasped, knowing instantly that a vision of such crystalline glory expanding, opening for business, could only be a forecast of what was to happen within my bones; and so told me what I knew already, and wept as I wept.

So that made three: the first dream of my father's deadly betrayal, the second of this miraculous enterprise preparing to open, the third with my lover, sister, anima, planting new life in the dense tangle. I swear, these are the only dreams I've remembered since I read those first blood-counts five months ago, and each was an uncanny doozy. One can't get such signals by hoping or trying. I've been humbly awed, hardly able to grasp whether or how I've credited them in my deep reaches. I'd say that the strange calm and clarity and steadiness that have organized my attitudes through the whole of this crisis began at once, and was only reinforced by the sequence of their signals – but really, it began with the first, my acceptance of my terror – so how can I know what part they've played in the whole, what I've made of them, what they've made of me?

******

Meanwhile, while I rested after chemo, Devora injected her belly fat for the fourth day with colony-stimulating factor, to spur her stem cells into crash multiplication and force them from marrow into her peripheral circulation. On my second day of rest, they harvested her. She mostly dozed during five hours as the tubes diverted its flow through the pheresis machinery and back again, but got a bit restless at the end. Bridget said she'd never seen such a harvest, but Devora thought she was just funning her until I called the next day and she said, "really, it's about the best I've seen in ten years, there's more than enough to freeze for a second try if we need it. Your case is blessed," or something like that. Struggling all day with computer glitches, I looked up too late to sit with Dev through her last hour as I'd meant; but she came by my room after dinner, and we hugged in glad thankfulness and humility, looking to the morrow.

They count down from Day –8 through chemo Days –7 to –3 through the rest days to call the transplant day Day 0. Some call it The Day of My Rebirth, but there's nothing dramatic to watch, just another bag dripping from a pole into one's vein for twenty minutes. Karen had to work, but Lorca and Jared were there with me, and Devora came with a bottle of Martinelli's sparkling cider. I located and downloaded our family celebration song, Purcell's "Come, Ye Sons of Art," in barely enough time to start before the drip began,; and we shared laconic Martinelli toasts -- the most meaningful being our ancestral Jewish toast, "L'Chaim!" ("To Life!") -- beneath the tumbling of Purcell's glad cadences.

.

.

Devora bountiful

The mush in the bag was an odd rosy color, not at all like the tan of bagged platelets that I had expected. The small bag held only seven million CD34+ stem cells; it ran out before Purcell's final cadence. We hung around only briefly before we hugged and the others dispersed, leaving me to do markup on science lessons before hacking at the laptop's illness again. By late that night, I had somehow got the drives to open properly on double-clicking, and thought briefly that I'd cured the bug, until it popped up in a new place to collapse a program, whereupon the nurse came by to divert me by taking my midnight vital signs, freeing me to collapse myself, my frustration dissolving in a sense of wonder and hope at what might be happening within me.

******

My Sister's Note, the Day After

Dear Turtlebug,

This came to me, driving home.

Love,

Devora

Stem Cell Transplant

for my brother Michael

The color of my cells

dripping into you,

that rosy mush we

couldn’t really describe,

was exactly the color

of the pink rainbow

on the stippled side

of a trout seeking

habitat among

the rocky crevices

of a new stream.

.

(Tears sprang from my eyes

like trout startled by

her precise splash

of metaphor.)

.

******

And so began Day 1 et seq after transplant, waiting to see whether and when engraftment might occur. I was sure it would take a long time, at best, to take and become productive, given the state of my marrow, the rarity of my condition.

It was only after the third time that Jeff Wolf told us proudly how he'd been the first hematologist to cure a case of AML with advanced fibrosis, publishing the very first report – on some 27-year-old girl whose fibrosis dissolved completely after her transplant took -- fully thirty years ago by now, that I came to wonder, and then to get it: surely if he'd cured another since, he'd have said so too. I forbore to tease him, but said only, "Hey, you save me and you'll get another bookend paper for the art, the youngest and the oldest saves on record." Two months later in hospital I asked straight out how many such cases he'd seen before me. Just five in thirty years, he said.

If I didn't bother to ask whether he'd saved another since the first, it was because I already knew, and had been prepared to know. After the first alarming report of my counts, I had been reading, and so had Lorca. As I had ransacked the technical literature of tumor treatment to understand his condition and seek some therapeutic edge so long ago, so he ransacked it for me now, with more powerful tools of computer grasp and professional access to online resources beyond my reach. By the time he slowed down, I had been through a foot-thick pile of offprints from the ongoing conversation of hematological research and treatment, and so had he, learning enough to home in on three half-plausible diagnoses, and to understand that Wolf's choice was nearly arbitrary, and that this hardly mattered, as all three amounted to the same problem, with only one answer as to what to do.

The kindest reports of transplant treatment for people older than fifty with ordinary forms of AML (Acute Myelogenous Leukemia) put one-to-two-year survival statistics at 31% or so. By thinking that I was in relatively good shape, and had such good support and treatment at a class institution, I could fudge this figure imaginatively up to 51%, more likely life than death, if only barely so. But cases with advanced fibrosis were so uncommon that we never did find a paper evaluating treatment outcomes for even a small series. All I could find were the many references testifying that advanced fibrosis was yet another dismal prognostic factor, on top of my age and the high number of mutations in my malignant clone, likely canceling out my optimistic fudge.

I hardly winced, for all I wanted was what numbers there were, whatever they were, to see what was what as I went along, already certain – from the first – about what I had to do. But I winced indeed as I thought of Lorca reading the same papers, understanding them even better than I, with the 31%s raking like brambles across the naked eyes of his heart.

[Suffering? Oh, my!]

So I was expecting engraftment to take a long time, since Jeff agreed that fibrosis was likely to slow the process. In the meantime, what I was waiting for as the numbered days marched on was to get hammered by the side-effects of the chemotherapy I hadn't felt. Chemo targets fast-dividing cells democratically, affecting not only malignancies but regular blood-making cells and hair and all the mucous tissues, including the digestive tract from lips to anus. It takes a while for the inflammations and ulcers to begin appearing. In the mouth, they're called stomatitis; all the rest of the way mucositis is the term, from mild cases to severe ones torturing intestines to bloody diarrhea. I was glad my protocol hadn't included radiation, which makes these afflictions even worse – though I wouldn't have wanted to agree to that anyway since it tends to make people stupid.

So I'm waiting to feel chemo's after-effects, and nothing keeps on happening as Day 5 turns into Day 6. I do have a day and a half of slight malaise, but this hardly affects me as I manage at last to load a whole first version of my website from desk to the distant server. I plug the URL http://mrossman.org/ into my browser, and see my front page appear on the screen just as everyone else's does – albeit so bare and primitive, with just a few titles linking to the texts of two new books on thirty years of teaching science, forty-some of writing about the Free Speech Movement. Stoked, I down some Tylenol, thinking a slight ache from internal battering might underly the malaise; that failing, I go back on anti-emetics, and it disappears. I'm still eating ravenously, making the best of the mediocre food here, chowing down more than I do at home, as I've done ever since I came in hospital -- and my weight's still dropping, I've lost ten pounds of fat around my middle while sitting in front of the screen and riding a bike for five minutes twice a day when I remember. No one has any idea of where the fat-energy's going, but why complain? I'm trimmer than I've been for many years.

Meanwhile, I've been charting my daily blood counts. The long decline of my red-cells and platelets concluded precipitously after the chemo, leaving my keepers to keep me going by transfusions every day or two. As for white-cells, you can't transfuse them. A nominal quorum of neutrophils are still floating around for days, but their protection is an illusion, for they've been disabled by the Busulfan. In reality, I've been profoundly neutropenic from Day 0 on, quite defenseless save for the antibiotics, anti-virals, and anti-fungals coursing through my system from the pills they keep me popping. On Day 1 I stop going out of my room to make microwave tea, even with a hepafilter mask, and just hunker down in my cell for the duration, insisting that every person who enters the door wash first with antibacterial soap, instead of the convenient alcohol-gel squirt that can't kill pervasive C. diff. Besides staff, I see only my family members and lover, each time wondering what germ-laden air they breathed on the plane or bus, what their last touch of my granddaughter might transfer.

But I'm still feeling no pain, though a single painless sore appears on my palette by Day 7. The next day my free ride finally begins to end, with a sore spot on the side of my tongue. By Day 9, my uvula's ulcer is visible and a bother; but worse are the sore spots developing on both sides of my tongue at the root, so deep that the disgusting anaesthetic syrup can hardly reach them and doesn't do much good anyway. They hurt whenever I move my tongue to speak, and eating becomes progressively more painful over the next few days, to the point that I'm reduced to applesauce, yogurt, and two high-calorie, high-protein milkshakes on Day 11. After that, my tongue pain decreases steadily, faster than my appetite rebounds, leaving me now only with a sore uvula, healing more slowly.

as bad as it got

And that was the whole of my post-chemo pain. Though genuinely inconvenient and painful at meal-time for a few days, my stomatitis hardly amounted in sum to more than a bad case of strep throat, for nothing hurt when I wasn't trying to eat or to speak up. What bothered me more, in truth, was that I couldn't do any editing on my website. The program that had ported up my first draft had somehow left it unreachable; for days emails crossed between the server folks and my advisers, without resolving the matter, while I twitched, left only to more editing on my desktop.

So tote up my suffering during this whole ordeal: these mouth sores for a few days, and two brief spells of mild nausea during chemo, plus another one out of nowhere on Day 10. It was not quite a free ride all the way through, but seemed nearly as close to such as it's possible to come. I hardly know what to tell my friends who winced so deeply, imagining what I must be going through, except this truth -- and my wonder at being so fortunate in this regard, as in every other concerning this illness, except for the illness itself, which may some way in the end -- who knows? – prove fortunate too.

******

As for my hair, it finally started to fall out, though only from my head, just when the mouth sores were coming on – though this coordinated expression of chemo's damages was rather a coincidence, as quite different tissues were involved. I let random hairs fall for three days, and then sat smiling as Lorca shaved my head, remembering the wicked glee with which he had flung his loosened locks at his friends so long ago, and how it had felt to bend over him in the tub then, shaving him bald. He bore it with stoic grace thereafter, shrugging off the funky wig we got him in favor of a simple baseball cap, doffed at home. How deeply sweet it has been to have him companioning me so vitally this time around.

I regarded myself wryly in the mirror. I had rather liked my pixie cut before hospital; after fifteen years in severe long hair, it seemed quite upbeat. But this aging baldie, suspended between dignified and vulnerable? Oy. I saw myself as my mother's father Aaron so long gone, his blue eyes regarding me above a beakier nose, knowing so much more than he could say.

The next night, Jaime and Jayne came over. He had come down from Seattle three times, totaling almost half my time in hospital here, though he'd lost a few days from a cold, quarantined till we could be quite sure. Mostly we'd played Go, that infinitely subtle Tao-game whose bare elements I'd shown him so long ago. Lately he's taken it so seriously, rising in rank faster than anyone not Korean and starting at four has a right to. On the board we delighted each other, he with his startling depth of grasp of play and his tender tutelage, me as the promising novice responding to his care. So sweet!

But this last night, we set the board aside, as Jayne joined us in a truly collaborative design session. They giggled, mixing the henna, and then I froze as she applied it with graceful strokes, tracing a large peyote-bud on my crown with a Tao-sign as its center flower; and concentrically below, from brow to nape and round again, the great world-snake Ouroboros swallowing its tail; with ornate scales, scattered stars between bud and snake, and dangling forelocks of floral elements. Finally I looked in the mirror. Gosh, it looked distinguished indeed, in its quirky way. I wished the dark color of the henna itself would stay for weeks or months. From the time they left until breakfast, I did three long sessions on the bike, working up a sweat on my scalp and then wrapping my head in saran-wrap, in hope of making the stain be more intense. No such luck, only the pale ochre lines were left after I showered; but I no longer felt nearly so naked, preparing to venture back into the world.

|

|

========================

As for "Good News Comes in Twos": the other part is that my website http://mrossman.org is finally up, with a lot of substance but rudimentary cosmetics as yet. I'd appreciate any help in making it known to people who might be interested in the matters it focuses on -- for starters, my gathered writings about science education and about the Free Speech Movement, plus some writing about political posters (not yet illustrated, but that's coming). In particular, I hope for help in getting it linked-to from other sites; and in making it otherwise visible and attractive to search engines. If anyone has advice about book-publishers for the Science Ed and FSM books, that'd be dandy, as I'm totally out of touch in that way.

[Earlier references to unstable page URLs are now obsolete; any page on the site can now be bookmarked without fear it'll disappear.]

After so much frustration in hospital, how sweet to have it all working well!

.

Return to: Top | Leukemia Blog | Home

|